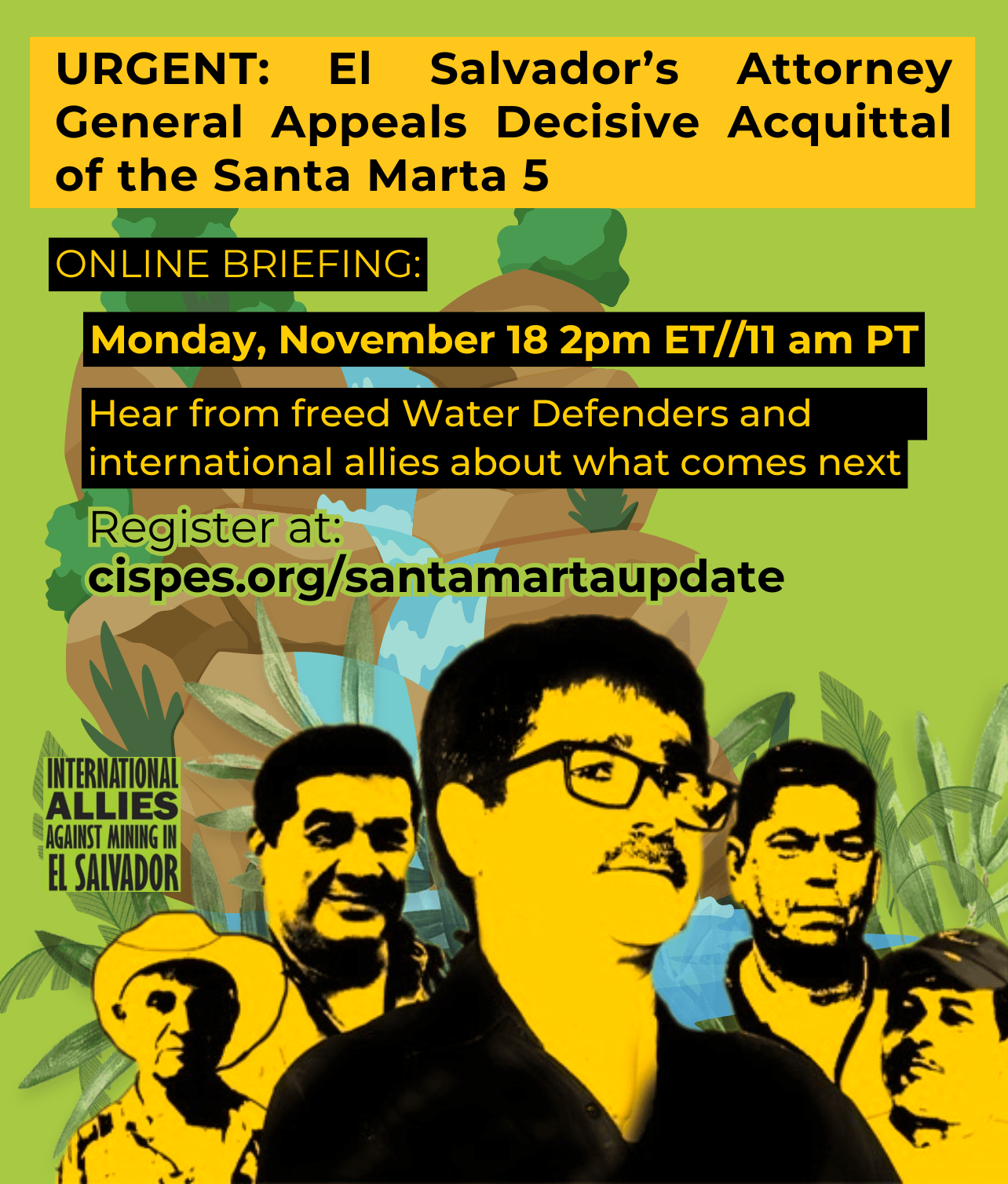

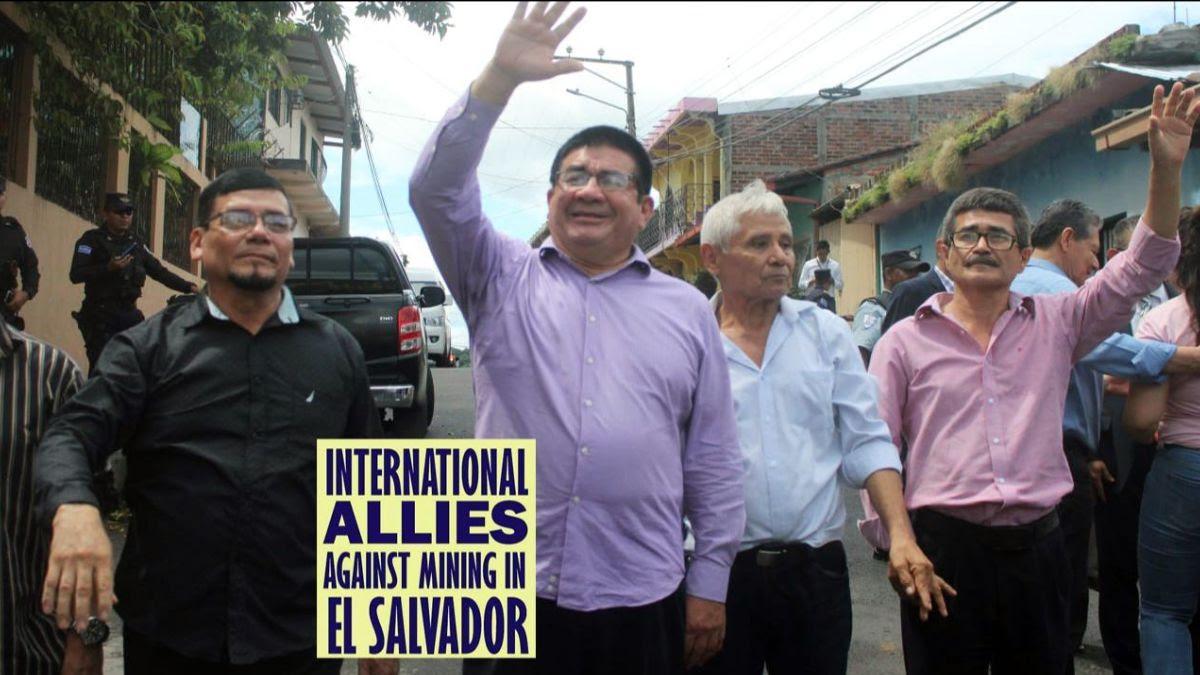

Join two of the Santa Marta 5 water defenders and representatives from the international campaign for an update of their legal case, and how we can support the Five.

Thousands of individuals and organizations from all over the world have worked with civil society groups in El Salvador for the freedom of the five Santa Marta water defenders who were unjustly arrested in January 2023 and charged with an alleged crime said to have occurred 35 years ago during that nation's brutal civil war. Finally, in October 2024, the five were found innocent of all charges in a court in northern El Salvador. However, the Salvadoran Attorney General has appealed this verdict to a higher court. We will discuss the case and ways the international community can support the Five.

(Spanish-English interpretation will be provided)

register here: https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZMvdOiprDouH9Ugdi5E3rB7_US2m4f4VX-x#/registration