by Adam Isacson

May 23 was to be the end of a shameful chapter in the recent history of human rights in the United States. Back on April 1, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had determined that the COVID-19 pandemic had eased sufficiently to make the so-called “Title 42” border policy unnecessary.

As of May 23, undocumented migrants apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border would no longer be rapidly expelled., Official border crossings (ports of entry) would re-open to migrants who fear for their lives. Asylum seekers would no longer be sent away in violation of U.S. and international law: they would have the opportunity to make their claims for protection.

That did not happen. Twenty-four Republican state attorneys-general filed suit in the court of a Trump-appointed district judge in Louisiana, who ruled on May 20 that the Biden administration did not properly terminate the emergency CDC measure. Because the ruling would require CDC to go through a public notice-and comment process in order to issue another ruling to terminate Title 42, it may now be in place until 2023 at the earliest.

Ports of entry remain closed to asylum seekers. Although another court ruling (Huisha-Huisha vs. Mayorkas) goes into effect today that requires the Biden administration to screen migrant families for protection needs, other migrants who turn themselves in to U.S. authorities asking for protection run a risk of being driven right back to the Mexico border, or being flown back to their countries of origin, to face the threats that they fled.

So far in 2022, U.S. immigration courts have granted asylum or other relief in 48.4 percent of the 23,590 cases they have heard. Title 42 has prevented tens of thousands of other cases from even being filed. This means there is a gigantic probability that the pandemic measure, which did not expire on May 23, has sent many people back to severe harm or death.

This is the most serious consequence of keeping Title 42 in place. But there are others.

1. The number of migrants arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border each month is now very unlikely to decline. It will remain near historic highs

Despite its harsh impact on asylum seekers, Title 42 has done nothing to limit overall migration at the U.S.-Mexico border. In fact, this migration is near record highs, and keeping Title 42 in place is likely to keep the numbers high for some time.

To understand why, we need to consider who is coming and what Title 42 means for them. This chart shows all migrants encountered by U.S. authorities every month since October 2011, broken down by whether they are single adults (blue), unaccompanied children (brown), or members of family units (green).

The chart shows monthly migration at ten-year highs (in fact, the highest levels since 2000). Considering these demographics separately, though, tells an important story about Title 42. First, here are migrants traveling as single adults, whom U.S. border agencies are encountering five times more often now than they were before Title 42 went into place.

Some of this sharp increase owes to a very large number of repeat crossings. Some single adult migrants are asylum seekers who turn themselves in to U.S. authorities. But single adults are more likely than families or children to be migrants who are not claiming asylum, instead seeking to avoid being apprehended.

For the non-asylum-seeking migrant population that gets sent back to Mexico, Title 42 has been a benefit. If Border Patrol catches them, they spend very little time in custody before being driven back to the borderline. Even if they have been caught more than once, there is no added sanction. They are free to cross again, and many do. In April, 28 percent of individuals whom Customs and Border Protection (CBP) caught at the border had already been caught at least once since October. Between 2014 and 2019, this “recidivism rate” was only 15 percent. Title 42 provides a strong incentive to try again, and the single adult “encounters” number reflects that.

Second, this chart shows migrants traveling as family units, or as children without parents.

Note that family and child migration, while high, is reduced from 2019. This is the impact of Title 42: families and children are likely to be seeking asylum, and U.S. authorities are using Title 42 to deny the right to seek asylum, expelling many. (The Biden administration is not applying Title 42 to non-Mexican unaccompanied children.) For asylum-seeking families, especially from Mexico and Central America, Title 42 has been a hardship.

If Title 42 should end, the number of asylum seekers, especially families, would probably increase. The number of non-asylum seekers, including many single adults, would probably drop sharply, along with repeat crossings. Border Patrol agents predicted exactly that in an exchange with Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas on May 17. Take these populations together, and the overall number of migrant “encounters” each month would most likely drop after Title 42.

No longer being able to expel migrants would mean more work for CBP personnel than they have to do now. Reopening ports of entry would require CBP officers to process asylum seekers again. Border Patrol, too, would have to process more asylum seekers than it currently is. And non-asylum-seeking migrants would no longer just be quickly expelled, they would have to be processed. DHS has made clear that it will seek to exact “consequences” on them, like immigration bans and even jail time, all of which would require CBP to do more paperwork. But that is how the border works, according to U.S. law—which remains suspended by a judge’s May 20 decision.

2. Protection-seeking migrants will continue to be forced either to cross improperly, or to wait for many more months in dangerous Mexican border cities

U.S. law clearly states that anyone who fears return to their country may ask for asylum once they are on U.S. soil. An asylum seeker may ask for asylum whether they arrived legally, approaching a port of entry, or whether they crossed between the ports of entry, which is a misdemeanor.

Title 42 has now closed the ports of entry to asylum seekers for more than 26 months. This has created an incentive for tens of thousands of asylum seekers each month to turn themselves in to U.S. Border Patrol agents “the improper way,” often by climbing the border fence or crossing the Rio Grande. These crossings are very dangerous: hospitals in San Diego have reported an alarming increase in deaths and injuries from border fence climbs, while drownings in the border river have been happening nearly every day. These dangerous crossings are now certain to continue, because the ports of entry are still closed to those seeking protection.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of migrants who wish to cross the “correct” way, by approaching the still-closed ports of entry, remain stranded in Mexican border cities, where data collected by Human Rights First show at least 10,250 reports of murder, kidnapping, rape, torture and other violent attacks on migrants since January 2021.

3. More migrants will come from “difficult-to-expel” countries, leaving Title 42 applied to only a minority of migrants

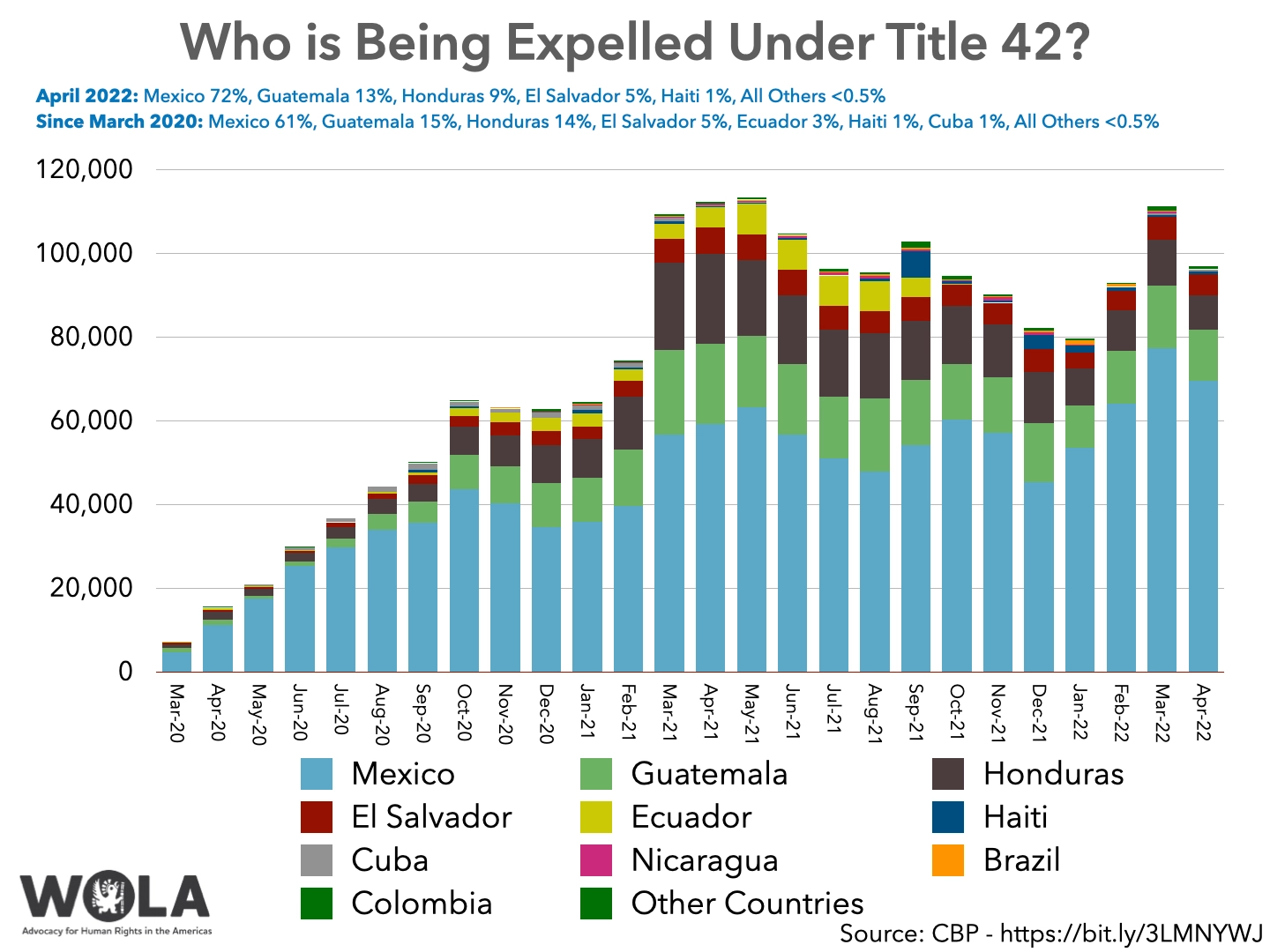

99 percent of the time, Title 42 gets applied to citizens of four countries. These are the countries whose citizens Mexico allows to be expelled over the land border into its territory: Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. (In early May, Mexico agreed to take a limited number of Cuban and Nicaraguan citizens as well.)

Those four countries made up only 54 percent of migrants encountered at the border in April 2022. (As recently as 2019, they always made up more than 90 percent.) The remaining 46 percent of April’s migrant population came from countries to which it is hard for the U.S. government to expel migrants.

It is “hard” because the United States may have poor diplomatic relations with their governments, as is the case with Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, the countries of origin of 37 percent of April’s non-expelled migrants. It may also be “hard” to expel migrants simply because their countries are far away, making it prohibitively expensive to airlift them. (The major exception here is Haiti: the Biden administration has forcibly airlifted 21,300 Haitians since September back to Port-au-Prince and Cap-Haïtien, where political instability and out-of-control gang violence make returned migrants very vulnerable. DHS has expelled 46 percent of all Haitian migrants encountered at the border since September.)

In either case, it means that if a migrant is from a country other than Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, or Haiti, they face little likelihood of expulsion. Instead, they get processed under normal immigration law, and most are released into the United States to pursue asylum or other protection claims.

In April, the Biden administration used Title 42 to expel 41 percent of migrants encountered at the border. That percentage will probably continue to decline to an ever smaller minority, as more and more migrants come from countries other than Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras, and as more families fleeing persecution and torture are screened and have the chance to seek asylum under the Huisha-Huisha ruling.

These are among the main consequences of Judge Robert Summerhays’ decision to keep Title 42 in place despite the CDC’s finding that public health no longer warrants it. For the next several months or more, a public health measure will serve as a backdoor way to curtail certain countries’ threatened migrants’ right to seek asylum in the United States. This decision will have devastating humanitarian consequences.