Thank you Alliance for Global Justice for sharing this article

By Becca Mohally Renk

[This article was originally published on the Casa Ben Linder blog at https://www.casabenjaminlinder.org/navigatingnicaragua/tr700abwmbf4hvks4lc05u75ewin6e .]

(Becca Mohally Renk is part of the Jubilee House Community, which works in sustainable development in Ciudad Sandino. The JHC also works to educate visitors to Nicaragua, including through their hospitality and solidarity cultural center at Casa Benjamin Linder.)

The capital city of Managua is a good lens through which to view Nicaraguan history. Its expansive views, shaded buildings, and streets with no name give us physical places to anchor our stories of colonization, inequality, insurrection, revolution and resilience. This is the fourth in a series about Managua.

I can’t take you on my favorite tour of Managua.

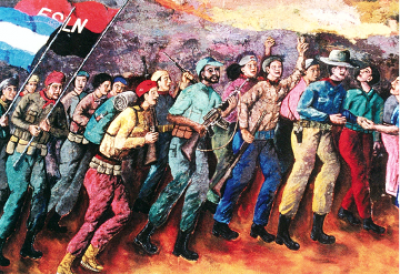

Avenida Bolivar, The Supreme Dream of Bolivar by Victor Canifrú and Alejandra Acuña

If I could, I would show you the Revolutionary Murals of the capital. We would start on Avenida Bolívar in the center of town and walk 100 meters down its length, watching Nicaragua’s history unfold beside us in full color in Victor Canifrú and Alejandra Acuña’s mural The Supreme Dream of Bolívar: Nicaragua’s first peoples, their resistance to colonization, the imposition of Christianity, liberation from colonizers, the United States depicted as Death, Sandinista guerillas fighting the insurrection against Somoza’s National Guard, and the building of the New Nicaragua in the Revolution. A mural flowing “in the very rhythm of revolution: impetuous, unreflective, disorganized, and energized.”*

The Reunion by Leonel Cerrato in Luis Alfonso Velasquez Park

The sun would be hot on our backs as we would turn into the Luís Alfonso Velásquez Park to see Leonel Cerrato’s emotional mural of Sandinista revolutionaries reunited with their families after the Triumph of the Revolution, Alejandro Canales’ multifaceted Homage to Woman and Julie Aguirre’s primitivist depiction of village life with campesinos learning to read. From there, we’d go on a driving tour because the murals we’d want to see would be spread around the city: in El Parque de las Madres, depictions of children demonstrating with the slogan of “paintbrushes against foreign interference;” at the airport arrivals terminal, a mural showing boys throwing Molotov cocktails and stones over barricades; at La Mascota children’s hospital, a mural depicting Vladimir Lenin fishing books by Malcolm X and Karl Marx out of a black pond.

We would end the day with a cold beer or sweet cacao drunk out of plastic bags in the shade, and we would reflect together on how these revolutionary murals are a visual embodiment of what Nicaragua was trying to become in the 1980s. Your eyes might tear up, thinking about how with the Triumph of the Revolution in 1979, the Nicaraguan people reclaimed national dignity and sovereignty and for the first time in 500 years became protagonists in the story of their own country’s future. You might be inspired, and rightly so. But your eyes will now probably tear up for another reason, because…

…these murals have been erased.

Of the nearly 300 murals painted in Nicaragua during the decade of the Revolution, most are now gone. In the “capital of mural painting,” Managua, murals were systematically painted over in the early 1990s – often under the cover of darkness – in an act of cultural imperialism that aimed to erase the Revolution itself and destroy the spirit of the Nicaraguan people.

Why did the new neoliberal government deem the Revolution so dangerous that all memory of it had to be erased? Let’s put that time in context. On July 19, 1979, the Sandinista-led insurrection finally overthrew the Somoza dictatorship, signifying the beginning of the Sandinista Popular Revolution.

From the beginning, the Revolution had its enemies: for the U.S. – which had backed the Somoza regime through five administrations, both Republican and Democratic – overthrowing the Sandinistas became a personal mission with the election of President Ronald Reagan in 1980. In the context of the Cold War, Reagan used any means necessary to try to accomplish this, including imposing an illegal economic embargo and training and funding a terrorist army of counterrevolutionaries: the Contras. Against all odds, the Sandinista Revolution was improving the lives of the Nicaraguan people through grassroots programs – providing universal health care and free education, eradicating polio through its vaccination campaign and eradicating illiteracy through its Literacy Crusade. To effectively attack the Revolution, the Contras attacked its achievements, the “soft targets” of schools, health clinics, and cooperatives; killing teachers, health care workers, farmers and children.

The Revolution was also cultural – after centuries of classist hierarchical art where oil painting was considered the only important art form, culture was democratized. Nicaragua created Centers for Popular Culture – 28 of them by 1988 – which painted murals, held poetry and pottery workshops, organized dance and theater festivals.

Thanks to the solidarity of muralists from around the world, a culture of painting murals was born, along with a Mural School which trained students and helped define the eclectic Nicaraguan mural style. “We did not want to ‘other-ize’ ourselves…or to serve the demands of the Western art transnationals,” said Raúl Quintanilla, artist, former Director of the National School of Plastic Arts and of the Museum of Contemporary Art. “We began to build a visual language embracing many dialects through…a dialogue that engaged everyone and everything, [dovetailing] social commitment and visual experimentation.” Although the murals were stylistically diverse, common themes emerged from the artists’ interpretations of the revolutionary process: dawn as a symbol of rebirth, parallels between the birth of Jesus and the birth of the New Man, and the triumvirate of books, hammers and guns to represent literacy, work and defense of the Revolution.

Particularly poignant in murals of the Revolution is the struggle of the indigenous people of Nicaragua and their resistance to Spanish colonizers, portrayed as parallels to the contemporary “Christian” persecutors, the Contras. In the murals, the colonial struggles were reexamined in light of the Revolutionary struggles; the indigenous of Nicaragua became models for the defense of popular sovereignty during the Revolution.

Colonizers the world over have for time immemorial committed cultural genocide in order to completely subject a people – prohibiting the speaking of indigenous languages, indigenous dances, indigenous clothing. In Nicaragua, this same practice was used to erase the murals that had fed and inspired the country’s revolutionary spirit for over a decade.

By 1990, nearly 50,000 Nicaraguans had been killed in the Contra War and Nicaragua’s revolutionary project was crippled by the economic embargo and derailed by the war. In the run-up to the February 1990 presidential elections, the U.S. made Nicaraguan voters’ choice clear to them: unless U.S.-backed candidate Violeta Chamorro’s party, UNO, won the elections, the economic blockade and the Contra war would continue indefinitely. George H.W. Bush’s administration poured money into UNO’s campaign to ensure its win. Scared and tired, when Nicaraguans went to the polls they voted to end the war: Chamorro won the elections, ushering in a 16-year neoliberal period.

After that election, Arnoldo Alemán became mayor of Managua. Alemán, a Somocista who spent time in prison during the Revolution, was fervently anti-Sandinista and had aspirations to the Presidency (indeed, Alemán became President in 1996 and his administration was so infamous – particularly in its embezzlement of Hurricane Mitch aid – that Transparency International named him the 9th most corrupt leader in recent history). As Mayor, Alemán made it his personal mission to erase the Revolutionary murals that had come to epitomize Nicaragua, sending municipal workers around the city to paint over any accessible revolutionary murals. Before they left office, the Sandinistas had declared many murals and martyr monuments to be historic patrimony, and therefore untouchable; yet Alemán’s municipal workers continued to paint them over in gray. It is rumored that the U.S. government donated paint to Alemán’s erasure project, and documented that Fuller O’Brien, a San Francisco-based company, donated paint “to obliterate Sandanista [sic] propaganda.” In 1993 – at a time when public schools were so underfunded that children had to bring their own desks to the classroom – great quantities of paint were issued by the Ministry of Education to schools all over Nicaragua with orders to use it to paint over any murals on school premises, most of which had been painted by the school children themselves.

It wasn’t just the murals, either, the neo-liberal government worked hard to erase all traces of the Revolution in the early 1990s: public school curriculum was completely overhauled and school textbooks were all pulped and burned, replaced with books that failed to even mention Sandino; books by acclaimed Nicaraguan authors were burned; the eternal flame over the tomb of FSLN Founder and martyr Carlos Fonseca was extinguished; later the monument itself was bombed as was a central public art piece, the Worker’s Statue.

In some ways, this strategy to erase was effective. After the elections in 1990, Nicaragua went into a kind of societal depression and the vast majority of families were crippled by extreme poverty, unable to plan beyond the next meal. While the country was incapacitated, the somocistas who had supported the former dictator oozed back into the country and violently stole back properties they had forfeited when they had fled Nicaragua a decade earlier. Violeta Chamorros’s government quietly erased the social gains of the Revolution, selling nearly all public enterprises at concessionary rates and effectively privatizing health care and education. She welcomed the World Bank and IMF and followed the letter of their structural readjustment programs, refusing to raise wages for teachers, police, or any public worker. She all but erased cooperatives by taking away their access to financing – when they could no longer work, they began to fold, and as those in the countryside lost their land they began to move into the cities looking for work. Gangs took hold in the cities, and crime rates – which had been all but nonexistent in the ‘80s – skyrocketed. The poor got poorer and the rich got richer until Nicaragua became one of the most unequal societies in the world. Desperate to find a way to earn a living, people began to leave in droves to Costa Rica and the U.S. until this small country had nearly 1 million citizens living outside its borders.

And yet, not everyone forgot. In hidden neighborhoods around Managua, the people kept watch over their Revolutionary murals at night, saving them from Alemán’s gray brush. Concealed from the public eye, new murals were born inside walls where they could stay safe. We’ll find some of these murals on our next Managua tour. [Ed. note: This article is coming soon!]

*Photos, quotes and information from Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua 1979-1992 by David Kunzle.