- Home

- About Us

- Issues

- Countries

- Rapid Response Network

- Young Adults

- Get Involved

- Calendar

- Donate

- Blog

You are here

Anti-Militarism: News & Updates

Event

March 25, 2022 to April 29, 2022

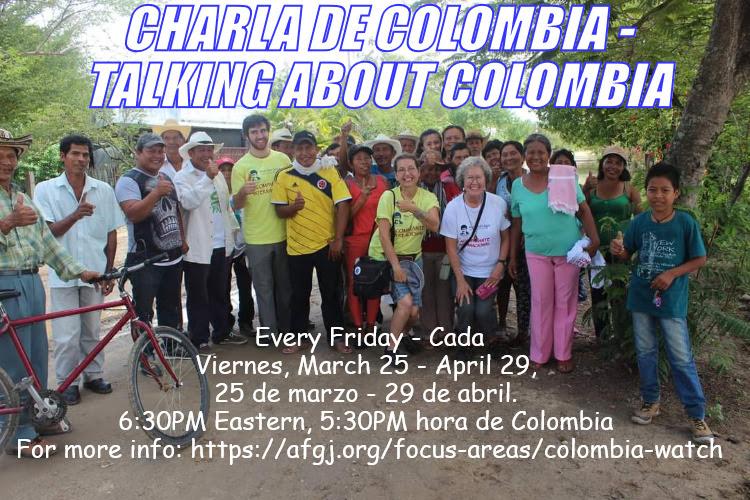

For the next six Fridays, AFGJ will be sponsoring a series of “Happy Hours”, each one an hour long, and featuring different social and political leaders who will help us understand Colombia’s elections and popular movements. These “Happy Hours” will not be your regular webinars where speakers give formal presentations followed by further discussion. Instead, the hosts and guests will share some social time together, conversing, as we learn details about the personal histories and lives of our guests interwoven with tales of struggle and discussions about their dreams and hopes for a New Colombia. Each show will also provide a chance for our guests to share some of the music, poetry, and other cultural expressions of resistance that help them keep their spirits up.

News Article

April 29, 2022

A group of prosecutors and judges who investigated the country’s most powerful officials in Guatemala has been forced to flee to Washington, D.C.

News Article

April 28, 2022

Gustavo Petro, a former left-wing guerrilla and the front-runner in Colombia's presidential election next month, is promising to shake up Colombian society. Disillusioned with the war, Petro took part in peace talks that paved the way for the M-19 to disarm and form a left-wing political party in 1990. Petro talks of raising taxes on the rich — and printing money — to pay for anti-poverty programs. To move toward a greener economy, he promises to stop all new oil exploration and to cut back on coal production, even though these are Colombia's two top exports. Petro has outlined a 12-year transition period and says the country could replace the lost income from fossil fuels with a major boost to tourism, and improvements in agriculture and industry. "I am proposing a path that is much better for Colombia," Petro told NPR.

News Article

April 28, 2022

A new database of incidents of abuse at the Mexico border paints a harrowing picture of the U.S.’s dysfunctional border security system and the “toxic culture” driving the law enforcement agencies tasked with implementing it.

News Article

April 28, 2022

Numerous politicians and scholars in the United States seem obsessed by, and perhaps even joyful about, the possibility that the world is entering a new Cold War, this time between their country and China. Some of these voices may believe that such a conflict could pave the way for a fresh Pax Americana, a beneficent world order led once again from Washington. But from a Latin American viewpoint, such a new era of confrontation must be avoided—and our countries should not be mere passive observers at this critical moment in history.

News Article

April 28, 2022

Colombia’s anti-fracking activists are facing increased threats and violence as two investigative pilot projects to extract oil and gas from unconventional fields move forward, five campaigners said, with some forced to flee in fear for their lives. Threats against activists are common in Colombia, which was the deadliest country for environmental and land defenders in 2019 and 2020, according to campaign group Global Witness. “Environmentalists have repeatedly reported that the authorities dismiss their complaints of threats and do not give them adequate protection,” said Juan Pappier, advocacy group Human Rights Watch’s senior investigator for the Americas.

News Article

April 27, 2022

Eleven Colombian ex-soldiers are giving details about extrajudicial killings carried out by the army during Colombia's armed conflict, as they are taking part in a public hearing of the special court examining crimes committed during the conflict. Néstor Gutiérrez was among six former members of the military who gave evidence on the first day of the hearing on Tuesday. Five more are due to appear on Wednesday. The six took responsibility for killing at least 120 civilians between 2007 and 2008 and passing them off as combat fatalities in the Catatumbo region, in eastern Colombia.

News Article

April 26, 2022

A federal court on Monday temporarily blocked the Biden administration from removing the order after several states filed a lawsuit to keep it in place, arguing that revoking it would "result in an unprecedented crisis at the United States southern border." Senior administration officials told reporters that "if and when the court actually issues the [temporary restraining order]," DHS will comply with it, adding that "we are really disagreeing with the basic premise." Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas said in a memo that, once Title 42 is removed, the administration expects that "migration levels will increase, as smugglers will seek to take advantage of and profit from vulnerable migrants."

News Article

April 25, 2022

Thirty days after El Salvador’s Legislative Assembly approved a state of emergency in the country in response to reports of rising gang-related killings, and in light of the renewal of this measure on Sunday, Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas director at Amnesty International said: “Over the last 30 days, President Bukele’s government has trampled all over the rights of the Salvadoran people. From legal reforms that flout international standards, to mass arbitrary arrests and the ill treatment of detainees, Salvadoran authorities have created a perfect storm of human rights violations, which is now expected to continue with the extension of the emergency decree.